Movements of American pocket watches differ in many details from their Swiss counterparts. Here we look at some basics about them, without getting lost in the many deviations from the standards. American pocket watches are a topic with a lot of interesting things to discover.

Contents

- History – very briefly

- The watch case

- The Dial

- Movement decorations

- Manufacturer and serial numbers

- Diameter in lines vs. size

- Movement designations

- Positive and negative winding

- Double Roller vs. Single Roller

- Safety Pinion

- Going Barrel, Safety Barrel, Motor Barrel

- Railroad Watches

History – very briefly

As early as 1839, the Pitkin Watch Company began to manufacture individual parts of a movement by machine, while others were imported. In addition to increasing production output, this was also intended to produce parts so precisely that they could be inserted directly into the movement without adjustment and could also be replaced if necessary. This industrial approach led to unprecedented success for the American watch industry. In 1859, the American Watch Company, which later became the American Waltham Watch Company, began manufacturing entire movements using efficient machine metalworking methods. By about 1875, a number of other manufacturers followed, such as Elgin, Adams & Perry (later Hamilton), E. Howard and the Illinois Watch Company.

It is estimated that a total of about 150 million American pocket watches of good to excellent quality were produced, almost 80% of them by the two large manufacturers Elgin and Waltham alone. By good quality, we mean movements with a Swiss lever escapement and at least seven jewels. In addition, there are about 500 million so-called dollar watches, watches of the simplest design, mostly with pin lever escapement and without jewels, from manufacturers such as Ingersoll or Ingraham. We will not deal with the dollar watches here. Maybe another time…

The focus of American manufacturers was thus on the efficient machine-supported mass production of good movements. In contrast to the Swiss, they were rarely or never engaged in complicated movements such as triple calendars, chronographs, repeaters or tourbillons. The market in America was large enough for the manufacturers even without these complications.

The watch Case

The difference between Swiss and American pocket watches starts with the case. In the case of Swiss pocket watches, the movement and case either came from a single source or a watch manufacturer, watchmaker or jeweler purchased movements and cases separately and brought them together. The customer was always presented with a complete watch for purchase.

With the Americans, the case and movement often came from separate manufacturers. The customer chose a movement with a dial and, separately, a matching case, and the seller then assembled them. The cases were standardized so that movements from different manufacturers, but of the same size, fit into the same case. This meant that the customer could start, for example, with a very good movement and a cheap metal case, and later replace it, for example, with a solid gold case. The question “who was the manufacturer?” of the watch, therefore, does not arise in many cases with American watches!

The following picture shows the labeling of a case made by the Illinois Watch Case Co. ELGIN is part of the brand name here and has nothing to do with the Elgin National Watch Co. of the same name!

From the mid-1930s onwards, however, complete American watches were sold directly by the manufacturer. The movement manufacturers either had their own case manufacturing or cooperated with a preferred manufacturer.

An essential part of this interchangeability was the winding stem, onto which the crown is screwed. In Swiss movements, this consists of one piece and is specific to the movement. It must always be cut to a length suitable for the case before the crown is screwed on. On American movements, it is divided into two parts. A square with the crown is part of the case, the matching inner square is part of the movement. So the movement fits directly into the case without any adjustments.

There are two different variants of cases and the associated movements. Open Face refers to the variant where the crown is located at 12 o’clock. It forms a straight line with the small seconds at 6 o’clock. This variant usually has no protective cover for the crystal, so it is open.

The Hunter or Hunting variant, on the other hand, has a hinged cover to protect the crystal. Accordingly, the crown is located at 3 o’clock, i.e. at a 90-degree angle to the small seconds at 6 o’clock. For Swiss movements, the two variants are called Lépine (Open Face) and Savonnette (Hunter). In both Switzerland and America, movements often come in an Open Face and a Hunter version, where the components are arranged slightly differently.

[source: Illinois Watch Company Illustrated Catalog 1923]

The Dial

For Swiss pocket watches, the dial and hands may be supplied by the movement manufacturer, but may also be procured by the watch manufacturer from another source. On American watches, they usually come from the movement manufacturer along with the movement. Although, of course, the latter could also obtain them from a third party manufacturer.

Dials of Swiss pocket watches usually have two dial feet, which are often fixed with so-called ‘sugar loaf screws’. These are located on the movement plate.

Dials on American pocket watches usually have three dial feet that are attached with screws on the sides, just like modern wristwatch movements. Three dial feet seems to be quite advantageous, since it is much more common to see chipping on the dial of Swiss watches exactly where the dial feet are located on the back. These chipping are caused by hard impacts, such as when the watch falls to the ground.

Movement Decorations

Movements of American pocket watches are strikingly often very beautifully decorated and visually appealing. This is probably because the customer bought the movement independently of the case. There, the optics was certainly an important decision criterion!

The decorations on movement plates, bridges and possibly other movement parts are called damaskeening or damascening, presumably because they are remotely reminiscent of the patterns in Damascus steel. The term does not describe a particular type of ornamental pattern, but rather a multitude of different variations. In Switzerland, if anything, special patterns, such as Geneva stripes or perlage, were in vogue.

Other elements, e.g. screwed chatons or a fine adjustment on the balance cock, naturally also contributed to the visual appearance of a movement.

Manufacturer and Serial Numbers

If the manufacturer of a Swiss work has not kindly left his name or a logo on the movement, these movements can often only be identified with appropriate literature, such as the Flume Werksucher. And sometimes, unfortunately, not at all. In my collection there are about 70 movements that I have not been able to identify so far. And serial numbers, which can be used to find out more about the movement and its production period, are rather rare with Swiss movements, mostly rather with the high-quality manufacturers.

American movements usually have the name of the manufacturer and also a serial number hallmarked. Thus, a lot of information about the respective movement can be found via corresponding documents of the manufacturer. Among others, here: Pocket Watch Serial Number Lookup & Info | Pocket Watch Database

Diameter in lines vs. size

Measuring the diameter of watch movements in a metric unit such as millimeters would be too simple. For historical reasons, Swiss manufacturers still use the French line or ligne as the unit of measurement. Thus, a pocket watch movement with a typical diameter of 40.6 mm has 18 lines, also written 18´´´.

The American unit of measurement Size, on the other hand, is based on the non-metric inch. A movement with a diameter of 40.6 mm is then called 13 size, although this is a rather untypical size. Here, for example, you can find a list of size units:Pocket Watch Sizes & Measurement Chart: 18s, 16s, 12s | Pocket Watch Database

Often you also see the abbreviation s for size, e.g. 16s.

Movement designations

Until about 1900, many Swiss manufacturers often simply named their movements based on their diameter in lines, others had caliber designations even before that, which usually simply consisted of the manufacturer’s name and a number. A caliber number or caliber designation consisting of numbers and letters is still common today. Most manufacturers use the same caliber designation for different versions of a movement regarding the number of jewels, the decoration etc. IWC 73, for example, would be a complete caliber designation.

In America, a slightly different logic has prevailed. To clearly identify a movement, the diameter in size, the model and the grade are given in addition to the manufacturer. Model is a designation for the basic construction of the main plate, the bridges and the remaining movement parts. The grade, a number or a plain text name, describes the different versions of a model regarding the number of jewels, the decoration, the adjustment in various layers and possibly other features. Hampden 5/0 size Model 5 Grade Molly Stark and Illinois Watch Co. 6/0 size Model 2 Grade 903 are e.g. complete caliber indications.

Some manufacturers assign each grade designation only once, so that this alone uniquely identifies the movement. And often the model or grade also defines the diameter. So there is a rule and, of course, exceptions to it.

Positive and negative winding

Until around 1900, the key winding system that had prevailed until then was gradually replaced by the crown winding system, also known as Remontoir, both in America and in Switzerland. Initially, this still required an additional lever or pusher, with the help of which it was possible to switch between winding and hand setting when turning the crown.

The Swiss manufacturers usually prefer a small pin as a pusher on the side of the case, while the Americans use a lever under the dial, which sometimes requires the glass to be removed.

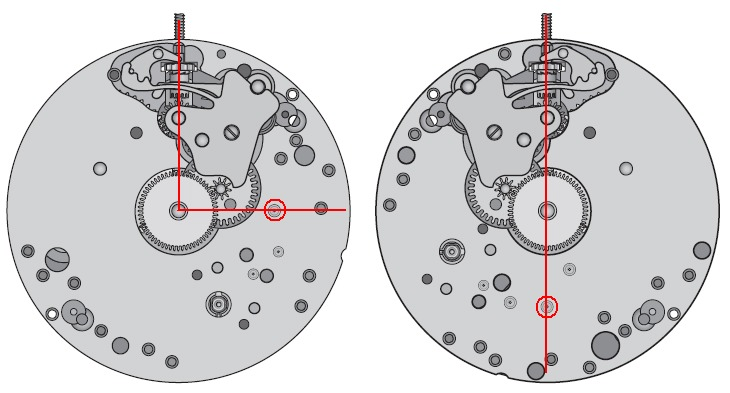

This was followed by the crown winding system as we know it today, which had become widely accepted by about 1915. It allows switching between winding and hand setting by pulling the crown. The realization of this switching mechanism differs fundamentally between Swiss and American in many cases. The Swiss use the positive winding system, the Americans prefer the negative winding system.

So where is the difference?

Swiss movements have a winding stem that is firmly connected to both the movement and the crown. On the movement side, the setting lever holds the shaft in the movement. This allows you to construct a mechanism in the movement that, when you pull the crown, causes the setting lever to jump to a different position, switching from winding to hand setting. A setting lever spring ensures that the setting lever remains in the desired position.

More precisely, when the crown is depressed, the position of the setting lever ensures that the clutch and the winding pinion are engaged and that the mainspring is wound when the crown is turned. When the crown is pulled out, the clutch and the hand setting wheel are engaged and turning the crown serves to set the hands. In the ‘normal state’ of the movement, i.e. when the crown is depressed, the movement is in winding mode.

American movements have a split winding stem, as described above. One part is stuck as a square, together with the crown, in the case, the other as an inner square in the movement. There is no fixed connection between crown and movement. Therefore, these movements do not have an setting lever. On a movement in disassembled condition, i.e. without case, the hands are set when turning with a square in the inner square. If you push the square a little bit towards the center of the movement, the movement goes into winding mode. In the ‘normal state’ of the movement, i.e. without pressure on the inner square, it is in the hand setting mode, so that one speaks here of a negative winding, compared to the Swiss movement.

However, the crown on American watches is usually designed in such a way that it presses into the inner square when pressed in, so the watch is wound when the crown is turned. If you pull the crown, the hands are set accordingly. The winding / setting mechanism is therefore different from Swiss watches, the position of the crown for winding or setting are the same!

Of course, positive winding also exists on American movements. Negative winding on Swiss movements, on the other hand, usually only occurs when they are made for the American market.

Double Roller vs. Single Roller

On American movements, you often find the inscription Double Roller. If there is a Double Roller, there is probably also a Single Roller. What is this all about?

The double roller, also called a plateau, is attached to the underside of the balance and has two functions. The larger roller, the impulse roller, carries the impulse jewel, also called the ellipse. This receives an impulse from the pallet fork at each half oscillation of the balance, which adds some energy to the balance to keep it oscillating. The second, smaller roller, the safety roller, is used to guide the safety pin, which is located between the pallet fork. It prevents the lever pin from catching on the outside of the pallet fork when the balance swings back, instead of being guided into the pallet fork. In this case, the movement would stop and the balance would have to be removed and reinstalled to fix this.

In the single roller, both functions are integrated on a single disc. The two different diameters of the discs of a Double Roller have small technical advantages, so that the Double Roller could eventually prevail. However, both variants fulfill their tasks!

Safety Pinion

Another inscription, which can be found relatively often on American pocket watch movements, is the Safety Pinion. It designates a special construction of the center wheel in the center of the movement and is intended to protect the movement from destruction of the gear train by the sudden release of energy in case of a break of the mainspring.

For this purpose, the pinion of the center wheel is screwed onto the axle of the wheel with a thread. If the mainspring breaks, the energy released is used to unscrew the pinion and thus prevent damage to the gear train. When the broken spring is replaced, the pinion can then simply be screwed tight again.

This design was patented as early as 1874 by Dietrich Gruen in American patent US157913. Gruen was German, emigrated to the USA and founded, among others, the companies Columbus Watch Co. and D. Gruen & Son in the USA and the Grünsche Uhrenfabrikation Grün und Assmann in Glashütte.

Going Barrel, Safety Barrel, Motor Barrel

The terms Safety Barrel and Motor Barrel can also be found on the movements of American pocket watches. Together with the Going Barrel, they designate three different designs of the barrel.

The going barrel is the standard version of a barrel as we know it from Swiss movements. The barrel arbor in the center of the barrel is used to wind the spring. When the movement runs down, it is not the axle of the barrel arbor that rotates, but the entire barrel, which in turn drives the pinion of the center wheel with its teeth on the outer edge. Since the axle of the mainspring barrel arbor only rotates when it is wound, it is rather pointless to provide its bearing with jewels. With a going barrel, the combination with the safety pinion described above makes sense.

In the case of the safety barrel, the teeth for driving the minute wheel are not connected to the mainspring barrel, but to the barrel arbor. When the barrel is wound up, it rotates, while the barrel arbor rotates with the teeth when the barrel is unwound. This has two advantages:

- If the mainspring breaks, the energy is discharged via the barrel without affecting the gear train. A safety pinion is neither necessary nor useful here.

- Since the barrel arbor rotates when the movement runs down, jewel bearings can be used effectively at this point. In addition to the technical benefits, the number of jewels can also be increased by two for advertising purposes.

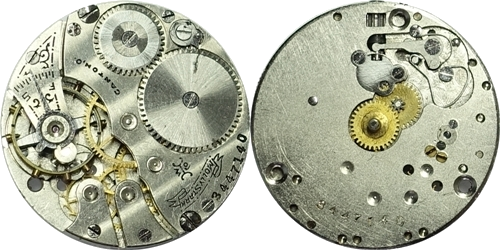

The motor barrel is functionally very similar to the Going Barrel, but is designed so that when it runs down, an axle in the middle of the barrel rotates with it, so it makes sense to add jewels to it.

The following picture shows on the lower left the mainspring barrel with the axle fixed to it, which can rotate in a jewel bearing when the movement runs down. On a going barrel, the rotatable barrel arbor with its axle, which does not move when the movement runs down, is located at this position. In the upper part of the picture, you can see the rather large barrel arbor of the Motor Barrel at the bottom of the barrel bridge, which does not move when the movement runs down. The axle of the barrel runs inside the barrel arbor.

However, if the mainspring breaks, the same problem occurs here as with the going barrel, so that the use of a safety pinion can be useful. Since the design is more complex than that of the going barrel, the motor barrel was usually only used in the high-quality movements of some manufacturers, e.g. Illinois or Hamilton.

Railroad Watches

Railroad watches and their movements are a particularly interesting subject among American pocket watches, as they generally contain high-quality movements. Railroads had a very great impact on the development of the American nation. The distances were great and the tracks were often only single track. Accurate watches were an essential requirement for train drivers and others involved to avoid collisions on the track.

There were many different railroad companies that defined their own standards and also some attempts to define standards across the board. All these standards have also evolved over time, so that the movement manufacturers have had to adapt again and again.

At the beginning of the 20th century, a standard could include, for example, the following elements:

- Open face with winding at 12 o’clock

- Arabic numerals, minute division, small seconds, large hands

- At least 17 functional jewels

- Only 16 or 18 size

- Maximum deviation of 30 seconds per week

- Lever for hand setting (instead of setting via crown position)

- Adjusted in five positions

- Fine adjustment

- Breguet hairspring

- Double roller

- Steel escape wheel

To go into the subject of Railroad Watches in depth would go beyond the scope of this article. If you start to be interested in American pocket watches, you will automatically deal with this genre. So have fun with it!