The manufacturer of the movement and the entire watch was the Waterbury Watch Co. from Waterbury in the state of Connecticut in the USA. The company was founded in 1879 by Daniel. A. A. Buck. As early as 1898, it was absorbed into the New England Watch Co. This in turn was bought by Ingersoll in 1914. It was no coincidence that a watch manufacturer was founded in Waterbury. At the time, the town was considered the brass capital of the world!

The company produced watches that were easy to make and therefore inexpensive, which is why the name Waterbury is often mentioned in connection with so-called dollar watches. We will see what was simple about the watches in a moment.

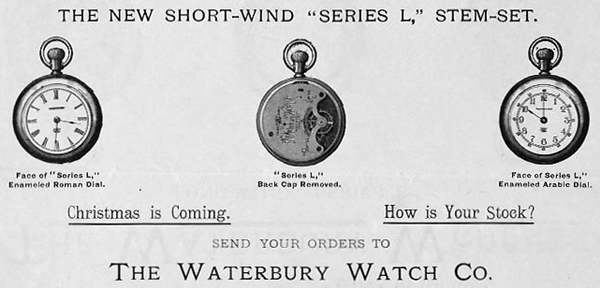

The watch shown above dates from around 1890, as the movement, a Waterbury Series L, was built from 1889 onwards. The following advertisement dates from this time, when about 300 employees were making around 1,500 watches per day:

After removing the movement from the case, two things immediately catch the eye. Firstly, the dial, which is made of paper that has simply been glued onto a brass disc. And secondly, the winding pinion, setting wheel and winding stem are part of the watch case, not the movement.

Oh yes, the watch does not have a second hand. This gives freedom in the spatial arrangement of the gear train and in the rotation speeds of the wheels, since there does not have to be a classic fourth wheel that turns once in a circle every 60 seconds.

The pillar construction of the movement is interesting, as it consists of five brass discs, including the one of the dial. So a particularly flat watch was certainly not the aim of the movement design.

Before dismantling the movement, the mainspring must be let down. This is done via the hole located on the bridge above the word Waterbury. If you turn the winding stem a little, you will see that the click moves there.

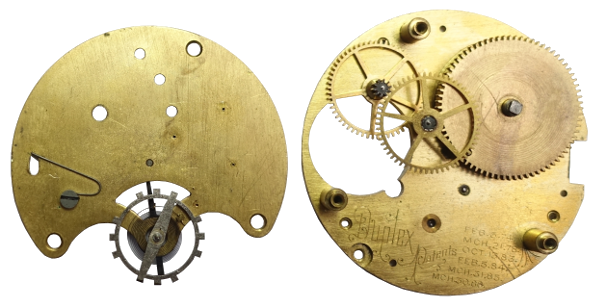

Let’s start on the dial side of the movement. This is what the movement looks like after removing the dial plate:

Apart from the hour wheel in the centre, there is not much to see, so let’s take down the next level as well:

In the picture above, the minute pinion is missing in the centre, which is driven directly on the dial side by the mainspring barrel (right above the centre).

On top of the minute pinion is the hour wheel, which is driven by the minute wheel on the left above the centre. This movement does not correspond to the classical movement construction, in which the center wheel is driven by the mainspring barrel, onto which the cannon pinion is pressed on the dial side, which in turn provides the necessary friction for the hands setting. The (almost) triangular spring on the barrel is responsible for this friction. In this case, the movement construction corresponds to that of a so-called Roskopf movement.

At the bottom of the movement there is an opening through which both the fourth wheel and the escape wheel of the duplex escapement can be removed. This fourth wheel does not rotate 360 degrees every 60 seconds!

Before we look at how the duplex escapement works, let’s disassemble the bridge side of the movement. Under the upper brass disc are the crown wheel, the ratchet wheel and the click with click spring.

The lower brass disc is at the same time the gear train bridge, the spring barrel bridge and the balance bridge!

Here you can also see very clearly that the balance pretends to be more valuable than it actually is: the screws are not screws at all, so it is a pseudo-screw balance.

The following picture shows the entire gear train from the mainspring barrel to the large driving wheel, the third wheel and the fourth wheel to the escape wheel:

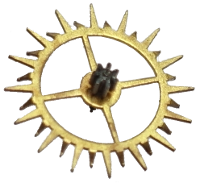

Let’s take a look at how duplex escapements work. It was invented as early as 1675 by Robert Hooke. However, it was not really ready for use until around 1750, after Jean Baptiste Dutertre and Pierre le Roy contributed to its further development. The name duplex comes from the escape wheel, which has teeth on two levels (see picture above). The large teeth serve the so-called rest. They engage in a tiny cut-out on the axle of the balance wheel and thus cause the inhibition, i.e. the periodic stopping of the escape wheel. The small teeth are used for the impulse phase, i.e. they periodically give a pin on the balance wheel a small push so that it gets energy for further oscillations. Whereas with the classic lever escapement, the escape wheel is moved a little further with each half oscillation of the balance, with the duplex escapement this only happens with each full oscillation.

On the website uhrentechnik.vyskocil.de of the watchmaker and watch manufacturer Volker Vyskocil there are excellent animations of various escapements. Unfortunately, since the animations are Adobe Flash files, they are no longer displayed by most modern browsers for security reasons. Here is a converted version as a substitute:

The following video shows the duplex escapement in action:

Accuracy records could hardly be achieved with the Duplex escapement. If it was made very precisely, the daily rate was perhaps one minute. In the case of the specimen shown here, it is more likely to be several minutes per day! Although the Duplex escapement was used in some English pocket watches and in larger numbers for the Chinese market, it never really caught on. So it only remained an evolutionary step in the development of escapements.

Back again to the Waterbury movement shown. There are numerous references to American patents on the plate:

Behind each of the dates are one or more Waterbury Watch Co. patents, each published on the same day:

- 03.02.1874: Patent not found online

- 21.03.1878: Patent not found online

- 13.10.1883: Patent not found online

- 05.02.1884: Patents US293018, US293042, US293046, US293078, US293079, US293142, US293143, US293168, US293169, US293170

- 31.03.1885: Patent US314834

- 30.03.1886: Patents US338959, US338960, US338961, US338962, US338963, US338964, US339051

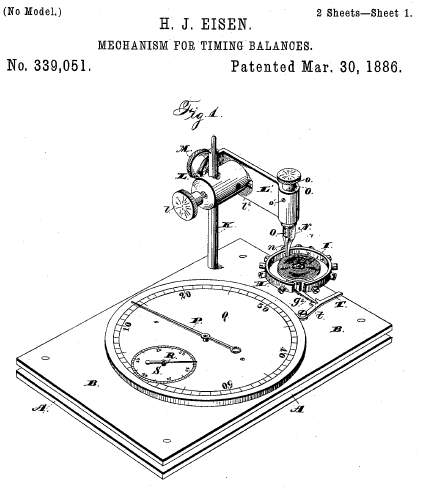

In total we are dealing here with at least 21 patents of the Waterbury Watch Co. which are mostly very generic and do not directly describe the movement shown here. For example, patent US339051 from 1861 describes a device for regulating balances:

Hi,

thank you for this article, I have been looking for this as I just collected my Waterbury pocket watch from repair. It’s a rare (I think) version of Series L in silver case and enamel dial made for British market.

Hi Andrew,

I am trying to service a series L but am having a hard time finding out what mainspring I should be using as a replacement for the one in the watch. Any insights you can share about the mainspring?

Hi,

I have no information about the mainspring for the Waterbury series L, but here you can find some information about the one for a series J:

http://www.ranfft.de/cgi-bin/bidfun-db.cgi?10&ranfft&&2uswk&Waterbury_Series_J&

I would try a similar size for the series L.