The most famous employee of this office might be Albert Einstein, who started his service in July 1902 at the age of 23 as technical expert third class. But it should not be about him here!

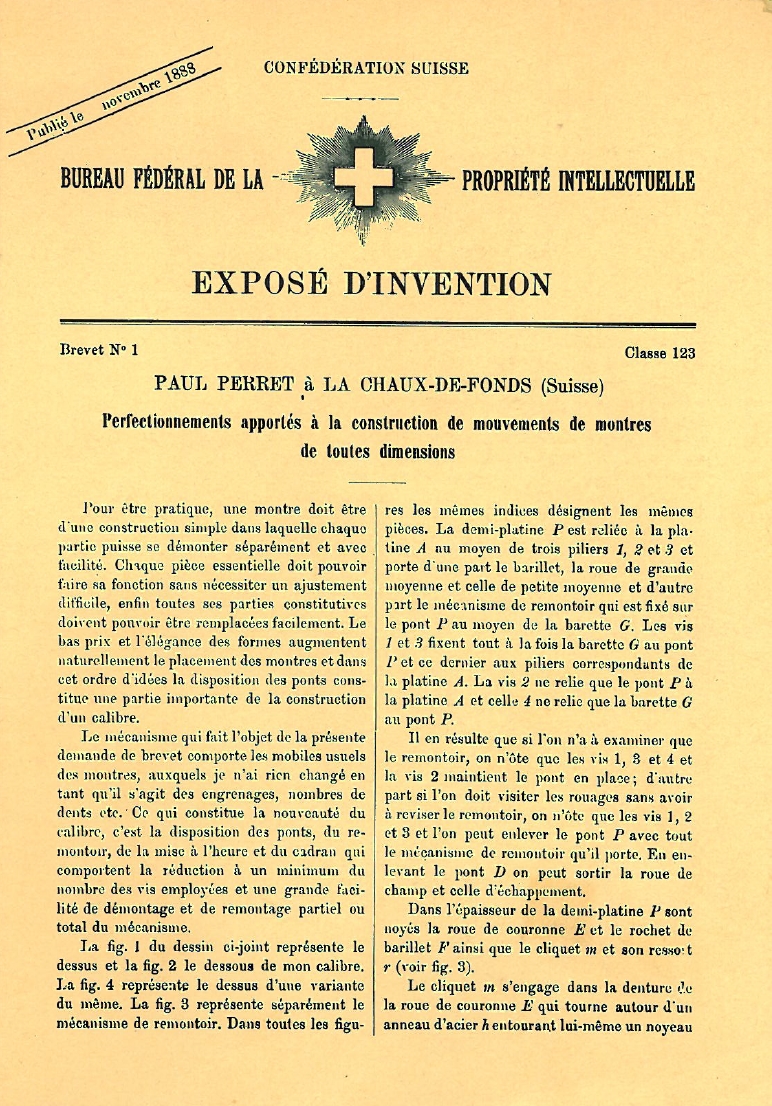

Already in the month of its foundation, i.e. in November 1888, the Office published Patent (French: Brevet) No. 1:

This first patent in Swiss history was granted to Paul Perret from La Chaux-de-Fonds for improvements to the design of movements of all sizes. In retrospect, this is a great tribute to the Swiss watch industry, whose importance even then extended far beyond Switzerland. Of the first ten Swiss patents, as many as four revolve around watches or watch movements.

Interestingly, for patent No. 1, the field for the date of publication was left blank (top left of the image)! From patent No. 2 on, this is filled in.

So who was this Paul Perret and what was the first Swiss patent about? We will see in a moment that Perret, although almost forgotten today, made a number of essential contributions to improving the accuracy of watches!

Paul Perret was born in 1855 in La Sagne, just a few kilometers from La Chaux-de-Fonds. Whether he did an apprenticeship as a watchmaker in La Sagne or La Chaux-de-Fonds is not entirely clear. La Chaux-de-Fonds was one of the watchmaking hotspots par excellence, but La Sagne also had several watchmakers at the time, who may even have had family ties to the Perrets.

As a young watchmaker, he then settled in La Chaux-de-Fonds and was mainly involved in the fine adjustment of pocket watch chronometers. He must have quickly gained a very good reputation in this field, as his customers included big names in the Swiss watchmaking world, such as Girard-Perregaux and Agassiz. At that time, participation in chronometry competitions at astronomical observatories was the opportunity par excellence for many watch manufacturers to demonstrate their capabilities and to advertise the results.

At the age of 33, Paul Perret was granted Swiss Patent No. 1. The title Improvements in the Construction of Movements of All Sizes doesn’t say much, except that it has something to do with watch movements. So let’s take a look at what it’s all about. The complete patent is attached at the very bottom of this article.

Perret explains in the introduction that this patent is about the arrangement of the bridges, the winding mechanism, the hand setting mechanism and the dial. This is done in a way that uses as few screws as possible and makes the assembly and disassembly of the movement as easy as possible.

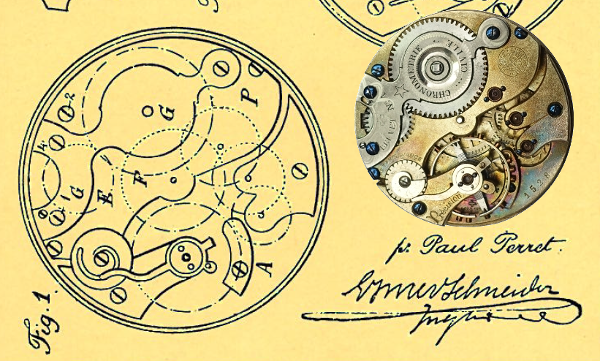

The patent includes, among others, the following drawings:

Often, patents contain only schematic illustrations of movements that were never built that way. However, the Perret movement from patent No. 1 really exists:

It has a diameter of 19´´´ (French lines), which is about 43 mm, and a height of 7.8 mm. In total, the movement has 15 jewels.

Unfortunately, I received the movement without case and without dial. The case probably fell victim to gold melting at some point.

The only significant difference to the patent is the way the hands are set. On the drawing of the dial side, you can see a lever at the top right of the winding stem, which has to be pulled to set the hands. My movement, on the other hand, has a pusher to the left of the winding stem (not visible in the picture), which directly pushes the setting lever down, allowing the hands to be set. So it’s a bit easier than the variant in the patent!

The cover clasp, which extends over the crown wheel and ratchet wheel, is inscribed BREVET No. 1 and CHRONOMETRIE CIVILE. The balance cock is also stamped with the word Précision. So, references to patent No. 1 and a high precision movement for civilian purposes. The high-quality impression of the movement is enhanced by the fine adjustment with cam disc and the screwed chatons.

By the way, the fine adjustment with the curved regulator, which rests against a cam disk, is not even listed as an invention in this patent. More about this in a moment…

There is also a PAUL PERRET PATENT mark on the barrel bridge, along with an image of a balance wheel.

This trademark was registered by Perret in 1888:

Here are two more impressions of the disassembly of the movement:

The mainspring barrel could therefore be removed directly through the large opening of the mainspring barrel bridge, without removing it. This is indeed very maintenance-friendly, as spring breakages were not uncommon in the past!

On the mainspring barrel, you can see rather rarely encountered Maltese-cross stopwork, which serves to ensure that the spring can neither be fully wound up nor completely run down. This ensures that only the part of the spring tension is used, which leads to a more or less linear power output to the gear train. This in turn directly affects the accuracy of the movement, but at the cost of a somewhat lower power reserve.

Another interesting hallmark can be found on this movement below the balance: 21.23.1967

What looks like a failed date at first sight, are the numbers of three other Swiss patents of Paul Perret: 21, 23 and 1967.

Swiss Patent No. 21 of December 5, 1888 revolves around the fine adjustment with cam shown above:

Patent No. 23, also dated December 5, 1888, covers the barrel design shown above, including the Maltese-cross stopwork:

Patent No. 1967 of April 15, 1890, further refines the principle of fine adjustment with cam disc:

But that’s not all, there are a total of 21 Swiss patents held by Paul Perret, the last dating from 1898, as well as various patents in the USA and Great Britain.

However, Perret was not only a gifted regulator, but also contributed to fundamentally improving the accuracy of watches. A detailed appreciation of his work would go beyond the scope of this article, so here are just a few keywords:

- Paul Perret developed the Talantoscope (spiral counter to determine the optimal spiral length) and the Campyloscope (a kind of pentagraph to magnify the shape of the spiral end curve in order to inspect it through a microscope) around 1875.

- In Swiss Patent No. 22 (1888), he describes a new, inexpensive way of producing compensating unbalances.

- He developed his own lever escapement (Swiss patent No. 12666 of 1896).

- Perret developed temperature-compensated balance springs from INVAR, a material invented by Charles-Edouard Guillaume for balances which, unlike steel, expands or contracts only slightly with changes in temperature. This earned him Swiss patents No. 14270 (1897) and 15526 (1898).

- In 1902, he founded the Société anonyme des spiraux Paul Perret à Fleurier to manufacture his balance springs.

Paul Perret died on 30.03.1904 at the age of only 49 in Landeron, Switzerland.

Finally, the Swiss Patent No. 1 in full beauty:

One thought on “Paul Perret and the Swiss Patent No. 1”